YEACHIN TSAI AND HER ART, By Sylvie G. Covey

INTRODUCTION

I met Yeachin Tsai in 2001 when she enrolled in the printmaking class I teach every week at the Art Students League of New York. After one week she announced that she felt the energy was right, comfortable and inspiring, and that she would stay. To this day she works among us but it is she who inspire us most.

Her presence radiates joy and kindness and is reflected everywhere in her work.

1. BACKGROUND

Yeachin Tsai was born and raised in Taipei, Taiwan. She graduated in 1987 from National Taiwan Normal University with a BFA.

Although she was already an artist at heart, her deep interest in people and humanity sidetracked her: she worked for two years in Taiwan as a photojournalist for a variety of magazines and newspapers.

Her subjects were always directed towards people, minorities, tribes, the expressions of feelings and emotions, and the condition of mankind. She learned much while traveling all over Taiwan. Her experience in photojournalism and photography deeply changed her internally. Viewing the world through people only, Yeachin started to view art as a communication language, and decided the art world was a privilege to earn.

A desire to open to the rest of the world prompted her to move to New York City in 1993, where she enrolled at CUNY Brooklyn College and received a MFA in 1995.

In 2001 she enrolled at the Art Students League of New York where she still pursues her studies in Printmaking.

2. INFLUENCES

Influences in art

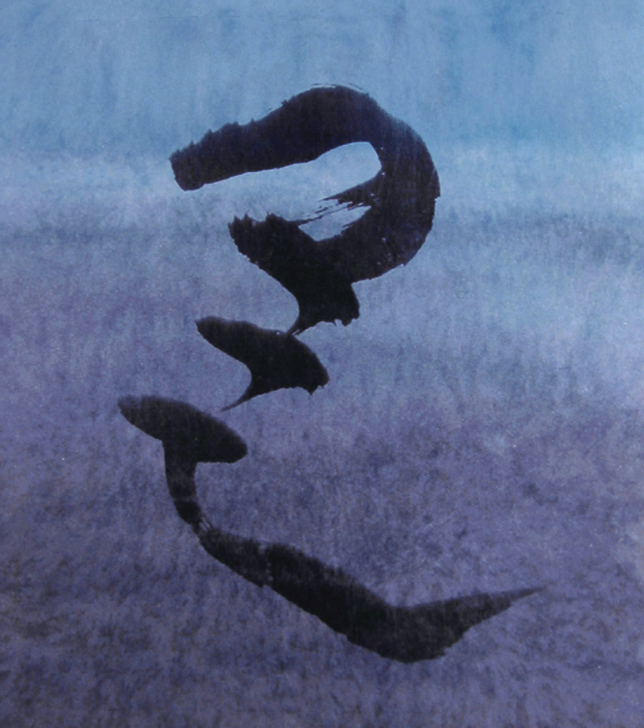

As a child and for twenty years Yeachin Tsai learned calligraphy and traditional Chinese painting through traditional Chinese Masters. Her arrival to the United States and her studies of Western Modern Art furthered her desire, in her work, to bring east and west together. This urge to find a bridge is her lasting theme and ambition, which evolutes and grows for the past ten years.

Modern influences from the west include Paul Klee, Matisse, Rothko, and abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock. Yeachin describes her effort to bring traditional Chinese

painting to the modern form by distinguishing the color, shape and form of a paint stroke, and cites Kandinsky’s book ”Spirituality In Art” as a great source of inspiration.

In modern painting, Yeachin feels all elements can stand out and the elements can be expressed separately and emphasized. By contrast, the Chinese language is very pictorial, with its pictorial metaphor: the language is about showing the essence of the visual objects and surroundings. She writes: “When the ancestors of the Chinese created the word “wind”, for example, there was a movement and power in the word itself. In a word like “fly”, you see the characteristic shape of the bird, and also the wavy air beneath the wings.”

After experiencing and struggling for years with different modern mediums such as oil, acrylic and wax with eastern imagery, but not getting anywhere near her bridge, Yeachin went back to her familiar material of ink and paper as a humility check. A new world opened when her brushstroke started to grow and find its own rhythm and tunes. She writes: “Every moment is totally new and unknown, full of possibility, like a river which is never the same current although it might look the same. The freshness encounter of paint and brush on paper or on silk is what I am looking for right now. It is neither Chinese nor Zen nor abstract; rather it is the map of this mysterious, transient, flux mind. It grows from Eastern tradition, but stands out as a child of endless human imagination, sensation, and longings.”

The Dance of Energy

In her work, Yeachin uses very simple strokes to express the most. When creating, she starts by emptying her mind and letting herself be open and still, so that the form she creates is all of herself from herself.

In order to communicate with others and further reach and understand herself, she gives a title and finds the meaning of the work after it was created, although many works are left without a title and description; those are left that way as if not born yet.

Working constantly through new shapes and forms, Yeachin sees the world as an energy field with all kinds of patterns interacting with each other, where nothing is fixed, nothing ever stays in one place, and describes her body of work as one continuous dance, a dance of life, a dance of energy. She writes: “I am fascinated by the flux of energy in all kinds of forms…I want to free the energy, let it be; or at least say hello, recognize it, see its dance in the infinite space, and dance with it – all I can.”

Influences of mind and spirit in the west

During her college years in Taiwan while struggling with modern paint mediums, Yeachin studied Zen Buddhism. After moving to New York City, her new life brought her to switch from the rigid and austere form of Zen Buddhism to the more gregarious Tibetan Buddhism, which is much more down to earth.

In order to make a living in New York she worked as a textile designer for many years. This led to socializing with western colleagues and friends, learning English and being part of the New York life and culture.

Yeachin started to realize that being alone was not helping her to grow and expand, and by contrast, sharing her feelings and her new life was what she needed. By opening herself to the culture and people of the west she gradually freed herself. In her artwork, the struggle disappeared as well, all started to fall into a natural adaptation and rebirth.

3. CONTENT, PROCESS AND MEANING

Bones

While in Graduate school at Brooklyn College, Yeachin decided to paint every page of a telephone book, making symbols out of abstract strokes. After a couple of years, looking back at these, she started to draw hundreds of similar ink drawings without trying to find any meaning in them. This was a breakthrough in her struggle to free herself from the rigidity and conformity of her Chinese background.

The last ten years in New York City have been all about freedom, finding herself in a new world she embraced. Yet she still seeks to find a bridge between east and west, by introducing the depth and strength of a simple gesture, a paint stroke, and compared her drawings to the bones of our soul.

Flesh

Starting in 2001 Yeachin decided to make prints out of the drawings from the breakthrough period. Various print processes such as photo etching, aquatint, chine colle and sugar lift are used to simultaneously preserve the purity of the paint stroke and create a new way to look at the symbols. Making prints out of the drawings resulted in important consequences:

First her drawings became color prints. The drawings were the bones, and adding color was like adding flesh to the bones, waking it to life. However some prints are still printed in monochrome tones because adding colors would bring too much energy to certain symbols. The monochrome tone then is used to reduce chaos.

Secondly the prints turned into series, each series conveying a specific metaphor. To work in series intensified the depth of the content of the work.

Yeachin’s metaphors come from our surroundings, nature, feelings, the diverse paths of life and our state of mind:

Crossing, Drifting, Flying, The Origin, The Seasons, Four Elements, Waking… Thinking, Seeing, Moving, Still, Echo, Island, Valley, Sky Dancer…

Life

At the same time, while continuing making prints, Yeachin’s paintings took on a stronger symbolism, clarity and purity. Her pursuit of spirituality is showing more than ever, and her paintings gained a light and luminous quality bathed in freshness and immediacy. Every stroke is done at once and never reworked, touching this perfect moment of existence. All the successful work is done very quickly, without thinking.

In “Landscape of the mind” for example, she let the brush stroke grow in the spaces and was aware of each mark around, so that the work reflects a total meditative state. She notes that in Tibetan Buddhism one meditates not to leave our surroundings but to achieve awareness and mindfulness in our state of being.

New Direction

After working so much in an abstract state of mind Yeachin recently felt the urge to express human feelings in a more tangible way, to go back and look at the people surrounding her. She now paints human faces, using ink on paper or tusche and water on polyester plates made for lithography.

Some paintings start with wax paper painted with ink and colored with oil layers on the back and the front. She uses wax paper rather than rice paper to achieve a deeper transparency and intensity.

The faces she paints convey as much depth and spirituality as her abstract work, in fact they convey a surreal, universal and undeniable lightness of being.

CONCLUSION

There is a profound quality and seriousness in Yeachin’s work, yet she succeeds in expressing the joy of life in all aspects. Through her paintings and prints she communicates her feelings with great sensitivity, strength, perseverance and dedication. I believe Yeachin is one of few who have found, in art as in life, her own voice.

Sylvie G. Covey

Sylvie G. Covey, an artist, master printer and printmaking teacher at the Art Students League and at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York